The Online Ass Wars

In an interview from November 2019, a spokesperson for Facebook, whose parent company Meta also owns Instagram, told me that it feels there are other platforms where users can post nudity and sexuality-related content. As became clear from the company’s Terms of Use update in December 2020, this kind of content was no longer welcome on the platform.

Banning everything from strip-club shows to erotic art, from self-pleasure to words alluding to sex, these new policies leave no room for interpretation: those trying to express themselves sexually or engaging in anything remotely similar to sex work should, for Facebook, take their posts elsewhere. And if they don’t agree to this, they – and their content – will be deleted.

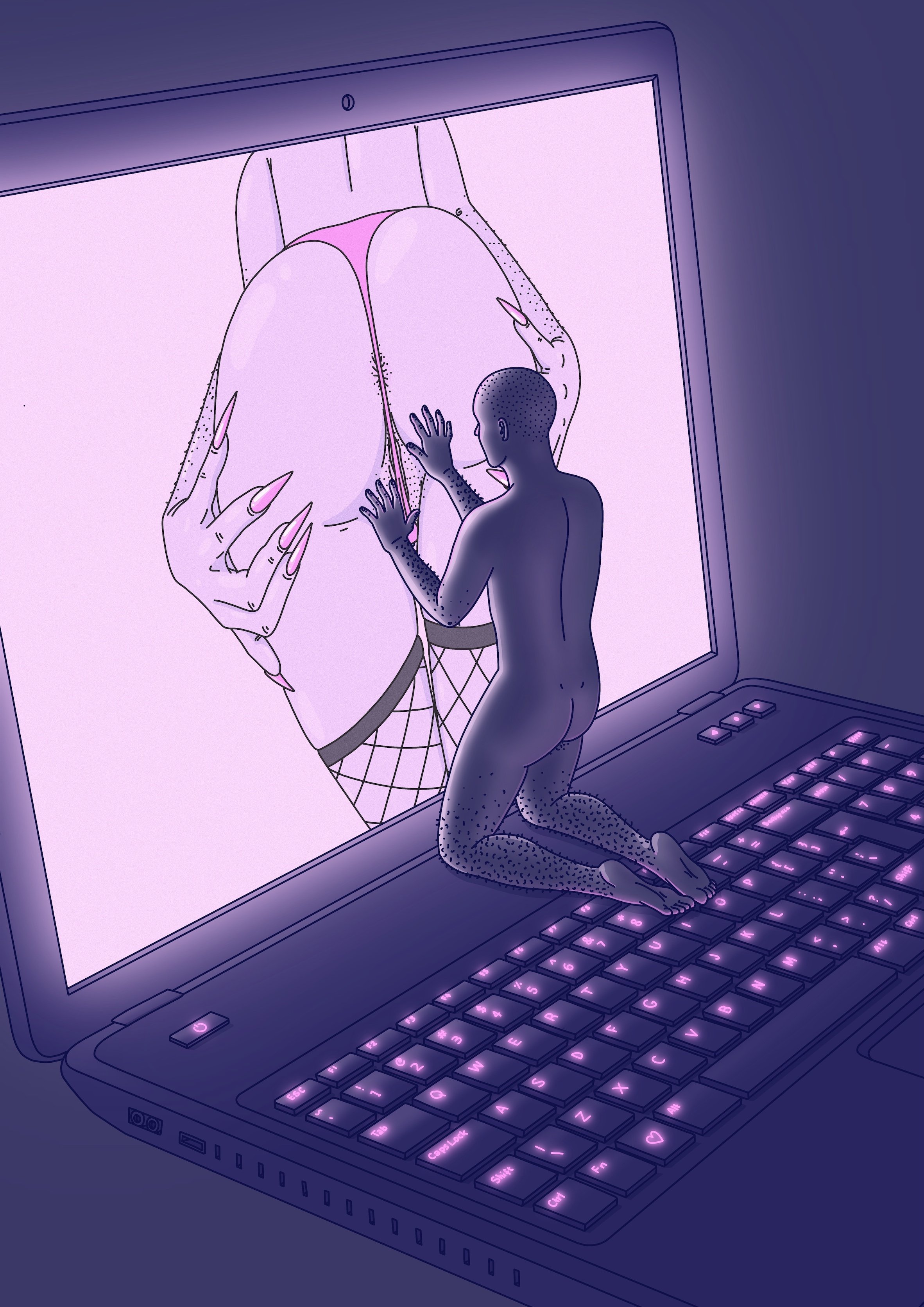

This stance is emblematic of how online platforms treat sex, nudity and sex work more widely. While they may initially let creators attract traffic to the platform through likes, follows and reblogs, once their brand has become sufficiently established, they tend to kick sexual content to the curb. Now there are a shrinking number of mainstream online spaces where nudity and sexuality are still allowed, making NSFW (“not safe for work”) content the hot potato that each platform is trying to pass onto the next. This fear of visible sex is spreading across mainstream internet spaces, resulting in censorship, deletion and decreased visibility of nudity and sexuality from Backpage to Tumblr, from Instagram to TikTok, all the way through to one of the most recent sites to have made its name on the back of online porn: OnlyFans. But these efforts to purge sex and nudity from platforms in order to win over advertisers, investors and payment providers – all carried out under the pretence of ensuring users’ and children’s safety – reveal just how much the affordances of platform design, and the laws and interests that influence them, can have disastrous effects on users’ income and their freedom of expression. Nudity and sexual content are being designed out of platforms, making it harder for it to be produced safely and ethically.

When OnlyFans announced in August 2021 that it was going to ban all sexually explicit content from its platform, for instance, it was big news. Not just porn industry, naked-social-media-subcultures news: big news, mainstream news. “In order to ensure the long-term sustainability of the platform,” the company explained, “we must evolve our content guidelines.” Citing concerns from its “banking partners and payout providers”, OnlyFans said that content creators would need to comply with its guidelines by 1 October 2021.

“It’s a big misconception that people who pay for sex work are bad people.”

By then, OnlyFans was a household name. It had been name-dropped by Beyoncé in a remix of Megan Thee Stallion’s song ‘Savage’ and quickly become one of the most interesting, if risqué, tech success stories since its foundation in 2016. As of June 2021, OnlyFans was locked in talks to raise new funding at a company valuation of more than $1bn, with its name having been made entirely on the back of home-made porn and sex workers, who had caused the platform to shoot to fame during a pandemic that made moving their work online a necessity as much as a privilege. In December 2019, the platform had a user base of 17 million, with this figure having risen to some 120 million by mid-2021. Meanwhile, the number of content creators rose from 120,000 in 2019 to around 2 million in 2021, with the site claiming that these creators had collectively earned more than $4.5bn since its foundation. “I’ve made more money on OnlyFans than I have on other platforms,” said creator @littlemistressboots to BuzzFeed in the spring of 2021, arguing that the subscription service helped them stay afloat after job losses during the Covid-19 pandemic. “It’s been a total game-changer for me.”

The platform had, for many sex workers, removed intermediaries such as production companies, pimps or club managers, bringing most of their earnings straight into workers’ hands. On top of that, it helped a variety of creators who couldn’t work traditional jobs make a living, too. Disabled user Sith told Chris Stokel-Walker at the New Statesman that, “[as] a disabled person, doing content creation allowed me to work from home and stay independent, while focusing on my health,” helping them to afford “life-saving medications”. Disabled Black sex worker Veronica Glasses, too, told Insider that working on OnlyFans has protected her from the racist and ableist abuse she received in strip clubs and on other social media platforms. “It’s a big misconception that people who pay for sex work are bad people,” Glasses said. “The majority of people being unkind are those who don’t think we need to be paid at all.” A side-hustle for some, the platform is now a lifeline for many, providing a haven from the censorship that sex work and nudity face on other mainstream social networks.

So when OnlyFans released a press statement about its ban in August, without even informing its main user base prior to making the news public, it made headlines worldwide. “Can they do that?” wondered some people and, perhaps even more importantly, “Should they be forced to do that?”

“We literally made you, @OnlyFans,” tweeted Rebecca Crow, a sex worker activist and performer, highlighting the anger present within the sex worker community following the decision. “I couldn’t sleep last night. As a creator myself I’m shook,” wrote Gemma Rose, a stripper, pole dance instructor and sex worker activist, on her Instagram. “Many are left baffled at why a business would ban their top earners,” she continued. “Are they really that desperate to ‘clean up’ their platform to attract top investors? Do they really despise [sex workers] that much, even though they are the reason this platform has become successful?”

OnlyFans claimed that it had decided to abandon its main nudity- and porn-based business model as a result of pressure from its payment providers. “The change in policy, we had no choice – the short answer is banks,” OnlyFans’s founder Tim Stokely told The Financial Times, arguing that it had become “difficult to pay our creators” given that banks “cite reputational risk and refuse our business”. When OnlyFans then performed a U-turn on its proposed ban in September, the decision was explained not in terms of any ethical shift or meaningful change in policy, but rather as the result of it having received the “assurances necessary to support our diverse creator community” from its banking partners. Inadvertently, OnlyFans had shone a light on the worst-kept secret influencing the design of content governance policy and infrastructure on tech platforms: that financial interests, combined with broad and flawed laws, affect what happens to users’ content far more than notions of safety or morality.

“Sex workers often build up the commercial bases of platforms, populating content and increasing their size and commercial viability, only to later be excised and treated as collateral damage.”

This may have been big news to the general public. As a pole dance instructor whose content is variously hidden, deleted and banned from social media platforms, it wasn’t news to me. Looking back over recent years, we can clearly track how nudity has become increasingly unwelcome on mainstream social media platforms – OnlyFans was only following suit from Tumblr, Facebook, Instagram and TikTok. OnlyFans’ decision was even less surprising to sex workers, who have had to be at the forefront of anti-censorship activism since day one as a result of the censorship and de-platforming that they continue to face.

But the truth is that sex workers and their efforts to distribute sexual content helped build the internet as we know it. The distribution of material depicting sex has long played a major role in the history of communications technology, from photography to home video and cable TV, when the sexual revolution of the 1970s collided with the birth of public-access television and increasingly affordable means of film production. It is only natural, then, writes the sexuality scholar Zahra Stardust, that sex workers were early adopters of the internet and social media platforms, variously “designing, coding, building, and using websites and cryptocurrencies to advertise [their work]”. “In our time of internet ubiquity,” Stardust adds, “sex workers often build up the commercial bases of platforms, populating content and increasing their size and commercial viability, only to later be excised and treated as collateral damage when those same platforms introduce policies to remove sex entirely.”

And yet, the (very necessary) efforts to regulate the internet have somehow become drenched in whorephobia, something which criminologist Jessica Simpson defines as “the hatred, disgust and fear of sex workers – that intersects with racism, xenophobia, classism and transphobia – leading to structural and interpersonal discrimination, violence, abuse and murder.” Stardust, as part of the Decoding Stigma collective formed with Gabriella Garcia and Chibundo Egwuatu, has also argued that whorephobia has become “encoded in tech design, despite the historically coconstitutive relationship between sexual labor and the development of digital media.”

Consensual sex work is clearly the wrong target in the urgent and vital field of moderating online harms. On 6 January 2021, groups of far-right extremists, Donald Trump supporters, and followers of the QAnon conspiracy theory stormed the United States Capitol to disrupt the formalisation of the election of Joe Biden as President. While the Capitol attack was a wake-up call for those outside of the tech industry, digital activism or online moderation research, it proved what many within those spaces had been warning about for years: that the lack of moderation of hate speech, conspiracy theories and misinformation that had already affected global political events such as the 2016 US presidential election and the Brexit referendum in the United Kingdom could have devastating consequences for democracy. So where had legislators and platforms been looking in their attempts to curb harmful content from the internet? Simple. They had been too busy fighting against ass. And they had been fighting against ass for so long that sex and nudity became both a scapegoat for, and a cautionary tale about, laws’ unintended consequences when it comes to online moderation.

When we talk about online moderation of nudity and sexuality, even on a global scale, we are really talking about the effects of the joint 2018 US bills known as FOSTA/SESTA, which have widespread implications for international platforms. The House bill, FOSTA, the Fight Online Sex Trafficking Act, and the Senate bill, SESTA, the Stop Enabling Sex Traffickers Act, are an exception to Section 230 of the US Telecommunications act, which ruled that “No provider or user of an interactive computer service shall be treated as the publisher or speaker of any information provided by another information content provider,” and should not therefore be held responsible for what third-parties posted on them. [1]

Section 230 is the legal provision that enables social media to exist as we know it, exempting platforms from the legal standards that traditional publishers are expected to meet. Except that, given FOSTA/SESTA, these online platforms would be held responsible for one type of post: third-party content facilitating sex trafficking or consensual sex work – the former being a crime, and the latter being legal, in different forms, in many countries (including the US and Canada, where jobs such as stripping have given birth to a lucrative night-time economy). Hailed by those who lobbied for it as a victory for sex trafficking victims, FOSTA/SESTA are exceptions drafted and approved in the United States, but they are being applied to the internet worldwide, having a chilling effect on freedom of expression.

“The term is a valuable and persuasive token in legal environments, positing their service in a familiar metaphoric framework as merely the neutral provision of content.”

The bills’ focus betrays a reflection of a US-based and sex negative mentality, as Kylie Jarrett, Susanna Paasonen and Ben Light identify in their book #NSFW: Sex, Humor, And Risk In Social Media. Social media moderation after FOSTA/SESTA is “puritan”, they write, and characterised by a “wariness, unease, and distaste towards sexual desires and acts deemed unclean and involving both the risk of punishment and the imperative for control”. Fuelling this, the argument runs, is a belief that sexuality is something to be feared, governed and avoided. This, for online sexuality researcher Katrin Tiideberg, blends with moral panics about children’s safety, and with “any resonant anxieties or moral panics that may be dominating a particular moment in time.” Just like previous moral panics about print media, television or pornography, the ability to find sex on the internet is the next big invention resulting in a push for censorship. As a result, sex work, which already suffers from lack of legitimisation and the attendant benefits of labour laws and protections, is being further stigmatised. It’s not just about the freedom to post ass; posting ass is both a form of expression and real work, and platforms fail to recognise this – having already reaped its profits.

Broad, flawed legislation inevitably affects platforms’ processes and designs, highlighting the weakness in social media companies self-defining as “platforms” in the first place. According to Tarleton Gillespie, a tech academic, the word “platform” is, mostly, a convenient shield for Big Tech. “‘[Platform]’,” he writes, “merely helps reveal the position that these intermediaries are trying to establish and the difficulty of doing so.” It is simultaneously generic enough to allow social media companies to paint themselves as tools that give the public a voice, to enable advertisers to reach bigger audiences, and to create spaces where users – and not the tech companies themselves – are responsible for the content they post. The word “platform” allows social media to appear virtuous and useful, all while shifting responsibility for any conflicts caused by users away from themselves. As Gillespie argues, “Whatever possible tension there is between being a ‘platform’ for empowering individual users and being a robust marketing ‘platform’ and being a ‘platform’ for major studio content is elided in the versatility of the term and the powerful appeal of the idea behind it. And the term is a valuable and persuasive token in legal environments, positing their service in a familiar metaphoric framework as merely the neutral provision of content, a vehicle for art rather than its producer or patron, where liability should fall to the users themselves.”

Social media’s self-definition as “platforms”, has been obliterated by FOSTA/SESTA. The bills have forced them to become overly conservative in their censorship of nudity and sexuality to avoid being held responsible, fined and blamed for wrongdoing. Sex trafficking – a crime with devastating human circumstances – needs to be fought, but it is striking that bills suchas FOSTA/SESTA also target consensual sex work. In their paper ‘Erased: The Impact of FOSTASESTA & the removal of Backpage’, the sex worker research collective Hacking/Hustling, led by Danielle Blunt and Ariel Wolf, write: “While the law has been lauded by its supporters, the communities that it directly impacts claim that it has increased their exposure to violence and left those who rely on sex work as their primary form of income without many of the tools they had used to keep themselves safe.”

Craigslist’ Erotic Services and Backpage were once a prime example of this new-found opportunity. These user-driven listing sites alllowed communities to list their services, giving sex workers more control over their work environment and avoiding some of the dangers of street-based work, such as different forms of violence by clients and the police. Blunt and Wolf write that internet-based sex work through sites such as Backpage “has allowed workers to be more forthright in their advertising, negotiate costs and services prior to meeting and establish boundaries.” Studies have shown that when Craigslist Erotic Services opened in 2002, murders of women in the US decreased by over 17 per cent in the following years. Because of this, the economists Scott Cunningham, Gregory DeAngelo and John Tripp have argued that “ERS created an overwhelmingly safe environment for female prostitutes – perhaps the safest in history.”

Even if FOSTA/SESTA technically became law only after Backpage closed its “Adult Services” section in 2017 (stating, “the government has unconstitutionally censored this content”), supporters of the bills argue that the removal of Backpage would not have been possible without them. And yet, as of today, only one charge has ever been brought to court under FOSTA/ SESTA: a June 2020 case against Wilson Martono, the owner of cityxguide.com, alleging “promotion of prostitution and reckless disregard of sex trafficking”, in addition to racketeering and money laundering. Meanwhile, the bills have worsened the conditions of the communities they claimed to be protecting: Hacking/Hustling found that after the bills were signed, and sites such as Backpage were removed, sex workers began facing the same old problems: “Sex workers reported that after the removal of Backpage and post FOSTA/SESTA, they are having difficulties connecting with clients, and are reluctantly returning to working conditions where they have less autonomy (e.g., returning to work under a pimp or to a 9–5 that does not accommodate for their needs or disability),” the collective write. In threatening legal liability for the promotion of sex work, FOSTA/SESTA have thrown platforms into a spiral of self-protection, resulting in designs that are based on over-censorship to protect their income, affecting swathes of internet content and behaviours with it.

Specific platform designs create specific affordances, or possibilities for different types of action. A forum may allow users to interact through questions and answers; the “live” function on social media apps makes broadcasting to live audiences possible; hashtags connect people with shared interests, and so on. These affordances were at the heart of social media’s initial pitch: through these functions, they promised, you will reach more people than ever before and have the chance to make your voice heard through channels that don’t gate-keep like the mainstream media. Inevitably, restricting or changing these specific affordances therefore affects the communities that use them. If you share and/or engage with content related to nudity and sexuality on the Internet, this is how FOSTA/SESTA affected you, making life on Facebook, Instagram, TikTok and Tumblr grow increasingly void of sex.

In 2018, for instance, the Tumblr “porn ban” removed sexual communities, fandoms, and groups that had developed over a decade; shortly afterwards, Reddit removed escort and “sugar daddy” subreddits, depriving users of forums where they could discuss this type of work. Facebook banned female nipples, triggering global #FreeTheNipple protests that forced the company to allow images of nipples in the context of breastfeeding, or breasts post-mastectomy and at protests. In many of these occasions, generic notions about “wanting to keep communities safe” and “welcoming” all sorts of users – rather than a direct mention of FOSTA/SESTA – were the platform’s main justifications for removing nudity from their feeds. “There are no shortage of sites on the internet that feature adult content,” said Tumblr’s CEO Jeff D’Onofrio in 2018. “We will leave it to them and focus our efforts on creating the most welcoming environment possible for our community.” Nudity had to go elsewhere, but that “elsewhere” continued to shrink.

It was a slippery slope that affected my own subculture, which left me in a unique position to research it. During the second year of my PhD in cyber-criminology, which focused on online abuse and conspiracy theories on social media, rumours of Instagram’s censorship of nudity began circulating in my networks of pole dancers and sex workers. It was early 2019, and the terms “shadowbanning” and “shadowban” had started to become bogeymen amongst the accounts I followed. Shadowbanning is a light censorship technique where platforms hide users’ content without notifying them. It can result in your account or your content being hidden from platforms’ main “Explore” or “For You” pages, drastically limiting users’ ability to grow and reach new audiences,and voiding the platforms’ pitch to not gate-keep views. The shadowban became a Twitter conspiracy theory when Republicans claimed the platform was restricting their content. However, while official platform statistics have yet to be published, a quick Google search reveals swathes of stories that seem to reveal it is actually women and marginalised users on platforms such as Instagram and TikTok who bear the brunt of this sly moderation technique.

In 2019, shadowbanning became a realistic threat to me and my network. I was just starting to make my name as a pole dance blogger and a rookie performer, and the online pole dance community had become a huge support network as I got out of and healed from an abusive relationship. Not reaching new audiences meant missing out on teaching, performing and blogging opportunities and, importantly, it meant losing my support network and the tools (platforms such as Instagram, where pole dancers connected through hashtags) through which I had learned the hobby that was increasingly becoming my job and my lifeline. That summer, I obtained an official apology from Instagram about the shadowbanning of pole dancing: “A number of hashtags, including #poledancenation and #polemaniabr, were blocked in error and have now been restored,” the platform claimed. “We apologise for the mistake. Over a billion people use Instagram every month, and operating at that size means mistakes are made – it is never our intention to silence members of our community.” However, as of today, the situation hasn’t changed. If anything, it has become worse, showing that limiting users’ views is actually one of the less damaging things that platforms can do to profiles.

Shadowbanning may be sneaky censorship, but it is nothing compared to outright de-platforming. Throughout 2021, my Instagram account was deleted once, my TikTok four times. In both cases, I received no warnings from the platforms that this was about to happen. My Instagram profile was deleted after I posted a picture with my 92-year-old grandma, leaving me at a loss as to how this had infringed community guidelines. In both cases, I only managed to recover my accounts by using my contacts and getting platforms’ PR and policy departments involved. Meanwhile, users who post nudity and sexuality are often deleted without warning like I was, but have no opportunity to communicate with platforms and find out whether they did, indeed, violate community guidelines or, as in my case, whether they had been deleted due to an automated moderation glitch. Account deletions of this kind often happen as a result of flaws within the design of platforms’ moderation systems, and yet leave the user very little agency to appeal, or even to understand what’s going on and learn from their mistakes.

“Viewpoints of communities of color, women, LGBTQ+ communities, and religious minorities are at risk of over-enforcement, while harms targeting them often remain unaddressed.”

Moreover, platforms’ design doesn’t target all users equally. In a 2021 Brennan Center report, Ángel Díaz and Laura Hecht-Falella wrote that “[while] social media companies dress their content moderation policies in the language of human rights, their actions are largely driven by business priorities, the threat of government regulation, and outside pressure from the public and the mainstream media. As a result, the veneer of a rule-based system actually conceals a cascade of discretionary decisions. […] All too often, the viewpoints of communities of color, women, LGBTQ+ communities, and religious minorities are at risk of over-enforcement, while harms targeting them often remain unaddressed.”

Research from the Salty newsletter has also highlighted how sex workers, LGBTQIA+ users, people of colour, religious minorities and activist organisations tend to bear the brunt of platforms’ moderation. “Compared to other marginalized respondents,” they wrote, “sex workers are most likely to report being censored in general.” Yet, while censorship of marginalised communities is rife, celebrities posting and profiting from risqué content and similar posts that would get a sex worker’s account banned are left to “break the Internet”. Facebook and Instagram are a case in point, as revealed in a recent Wall Street Journal investigation by Jeff Horwitz, who found that the conglomerate has “whitelisted” a set of high-profile accounts so as to ensure that they do not face heavy moderation. Quoting a 2019 internal review of Facebook’s whitelisting, Horwitz noted that the company acknowledged that “[we] are not actually doing what we say we do publicly[…] Unlike the rest of our community, these people can violate our standards without any consequences.”

Because hosting even the most remotely sexual content can be seen as a violation of FOSTA/SESTA, and may therefore result in expensive fines or legal procedures, platforms’ moderation of nudity and sex is rushed, automated and uninformed, leaving those who post it as the ultimate scapegoats in the war against online harms. As Netflix documentaries such as The Cleaners and books such as Siddharth Suri and Mary L. Gray’s Ghost Work have highlighted, platforms employ online moderators based all over the world, who likely have little or no subcultural knowledge about the content they moderate, forcing them to make split-second decisions about swathes of posts for which they are often paid per action. Having to flick through thousands of abusive, violent or graphic posts a day isn’t only damaging towards moderators’ mental health, it also doesn’t encourage them to take time with specific decisions. And yet, when a handful of platforms hold the reigns of most online content and online spaces, most users are moderated through the same approach.

OnlyFans’ move to ban explicit content revealed the driving forces behind the shrinking spaces for online nudity, showing how powerful lobbies can influence not just the law and Big Banking, but platform designs, too. Internet platforms are quick to make their money on the back of sex workers, but begin diversifying their audiences and trying to de-platform sex once growth with the general public becomes a possibility. OnlyFans’ move to censor explicit content does not seem so out of place when you consider that the platform had been attempting to diversify its user base for a while, welcoming Cardi B, RuPaul’s Drag Race All Stars winner Shea Coulee, and a variety of more “vanilla” influencers to show that the company did more than porn, prominently reposting these users’ content on its main feeds.

However, while something such as MasterCard’s decision to withdraw its payment services from PornHub in late 2020 received little attention from mainstream news, the attempted OnlyFans ban suddenly saw sex workers’ voices appear in articles. Through journalistic investigations and interviews with sex workers, the groups and campaigns behind these decisions were revealed: namely National Center on Sexual Exploitation (NCOSE) and Exodus Cry, which backed the recent #Traffickinghub campaign to shut down PornHub. As the journalist Chris Stokel-Walker wrote for Wired in 2021, “Exodus Cry, which reportedly has links to the International House of Prayer Kansas City, a hugely powerful American evangelical Christian ministry, lobbies businesses and politicians to crack down on porn. It does so as part of a twin-pronged goal: one noble, one less so. It presents itself as trying to mitigate the risks of sex trafficking, which should be applauded, but also seeks to use that as a method to halt all porn.”

Under the guise of fighting abuse, exploitation and sex trafficking, these groups – the same ones who lobbied for the approval of FOSTA/SESTA, gaining media traction by pitching themselves as ethical organisations that fight against online abuse and the non-consensual sharing of sexual images – want all sex off the internet. As part of this, however, they seem to have little interest in helping abuse survivors, so much so that they have been accused of saving and sharing child sexual abuse material by high-profile trafficking survivors who initially worked with them. One of them, Rose Kalemba, tweeted: “At first, the anti-trafficking movement felt like a lifeline. Hardly anyone had ever cared about what I went through before. But it quickly became yet another thing that would traumatize me.” In a post condemning the main advocates behind the #TraffickingHub campaign, Kalemba wrote: “You cannot uplift some survivors by oppressing others. You don’t protect children by punishing sex workers, many of whom are just trying to feed their own children. & you don’t spread awareness about exploitation by watching, storing & posting videos of someone being assaulted. You don’t cause harm in the name of survivors, harm that we’ve begged you not to perpetuate & have said we don’t co-sign, & then blame us by screaming ‘it was all for you! We saved you!’ & then running with the money you made off of our pain & suffering.”

The OnlyFans story dominated the news agenda for about a week before the company’s U-turn, highlighting the fact that online porn is still the platform’s main source of income. Despite the story’s brief shelf-life, however, it wasn’t only a watershed moment for online sex workers, who had relied on OnlyFans throughout Covid-19 lockdowns having already been de-platformed by nearly every other social network during a pandemic that had already closed down their offline workplaces. It was also a very avoidable public relations shambles, with mixed messages and a general carelessness that did the company no favours, making many of its customers jump ship despite its last-minute U-turn. In September 2021, Wired reported on the adult content creator Neville Sun, who had chosen to leave OnlyFans in favour of launching his own platform, NVS.video. “My heart was broken already,” he told Wired’s Lydia Morrish. “I don’t know if they will eventually or temporarily ban adult content creators. Next year it might happen again.”

Rather than the specificities of OnlyFans, however, it’s the general trend towards ridding internet spaces of nudity and sexuality that should stand as a stark warning. FOSTA/SESTA have forced platforms to not only look out for their advertisers’ interests, but mainly to protect themselves by over-censoring to avoid being seen as breaking the law. This has created an environment of “design by fear”, moderating quickly and without context – all the while failing to protect sex workers, creators and, as shown by Kalemba’s story, potentially even the trafficking survivors who the joint bill aims to protect. Now that swathes of business transactions, information sharing and just plain living happen online, we can no longer afford this: the world deserves better platform design that isn’t enforced by (and which doesn’t enrich) only a handful of companies, affecting the lives and livelihoods of millions of users worldwide.

1 See ‘On Censorship’ by Rianna Walcott, published in Disegno #27.

Words Carolina Are

Illustrations Exotic Cancer

This article was originally published in Disegno #31. To buy the issue, or subscribe to the journal, please visit the online shop.