Glass, Magic, and Realism

An illustration from Olaus Magnus’s 1555 book Historia de Gentibus Septentrionalis (History of the Northern Peoples).

There’s a legendary story that has passed from glassblower to glassblower at the Finnish glassworks Iittala. Back in the day, deep in the middle of winter, there was a drunk man who came looking for somewhere warm to spend the night. He found his way to the Iittala glassworks, where the door had been left open. He went inside, where it was nice and warm, and fell asleep. In the morning, the man woke up to see a flaming red fire pit and people brandishing sticks, moving around and working in perfect sync with molten lava – a beautiful but frightening choreography. He thought he’d woken up in hell and the glassblowers were the devils. He screamed and ran out.

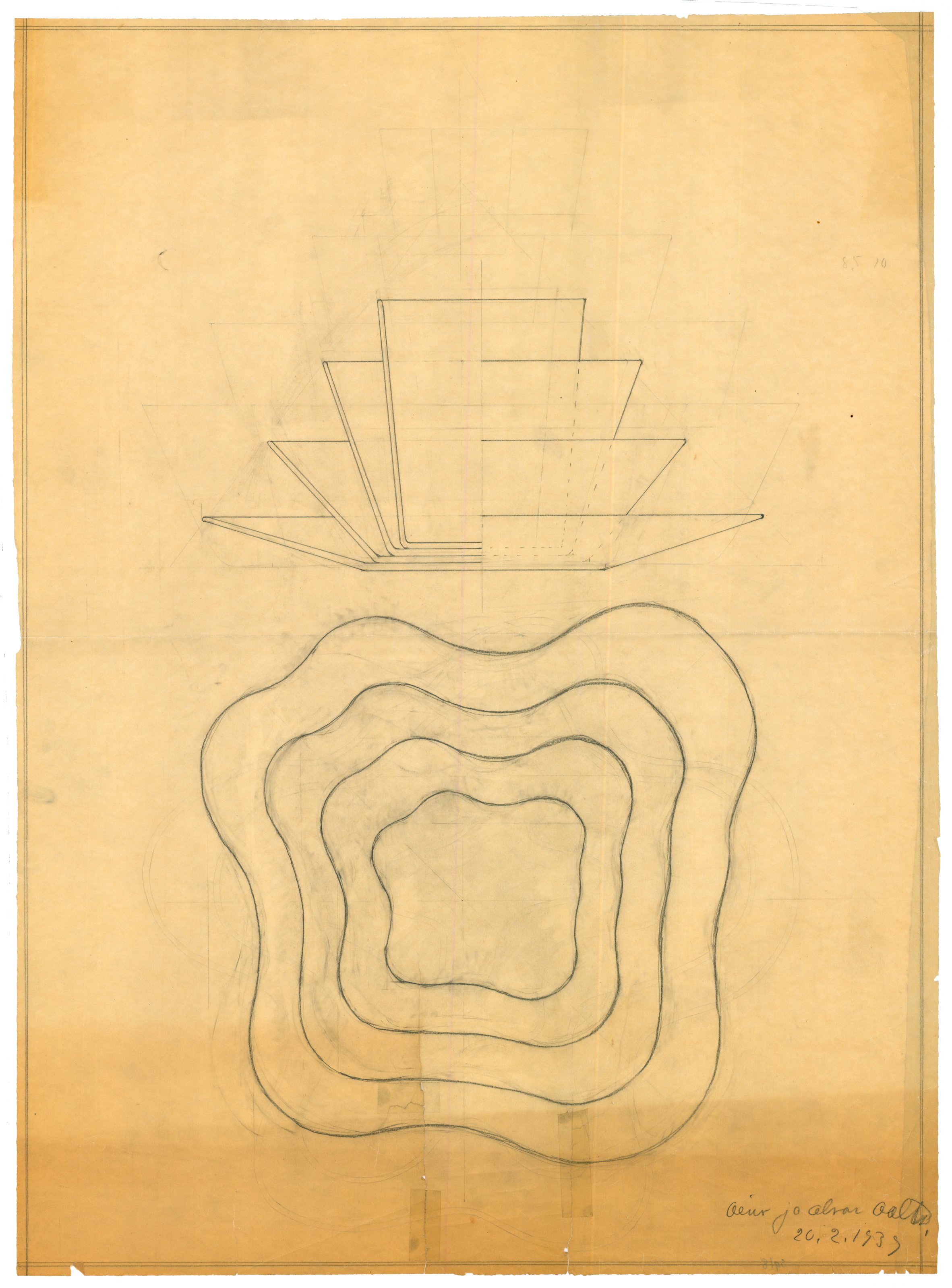

That story changes slightly every time it’s told, and we have probably changed it too, but it does capture something of the supernatural quality of Iittala’s glassblowing, and glassblowing in general. When we were asked to curate Iittala’s 140th anniversary exhibition at the Designmuseo in Helsinki, and produce a corresponding publication for Phaidon, we wanted to reflect this by calling the project Magic Realism. Although it eventually came to be called Iittala – Kaleidoscope: From Nature to Culture, the notion of Magic Realism came to define our approach. We wanted to show the slightly lesser-known aspects of Iittala: not just different variations of the Alvar Aalto vase and the Kastehelmi coasters and tableware that everyone has already seen.

In literature and cinema, Magic Realism refers to the extraordinary within the everyday, or the sublime within the normal. It doesn’t usually get used in the field of design, but it somehow seemed pertinent to Finnish culture and Iittala’s history in particular. It’s not an aesthetic category, or a formal category, but it does bring together many different elements and qualities that have been present in Finland for centuries or even millennia.

Historically, Finnish society has evolved with a reciprocal relationship to nature. This was an intense relationship that can be seen in the region’s prehistoric craftsmanship, and which remained interwoven with the country’s industrial development throughout the 19th and 20th centuries. Finland’s sawmills and forestry companies were generally interlinked with the glass factories, because the glassworks used the waste from the sawmills for fuel, and they all relied on the same logistics: the rivers, waterways, and lake networks. The affordances of the surrounding environment – climate, landscape, flora and fauna – informed both belief systems and material culture. Magic was pragmatic.

On one hand, these ideas became visible in the Kalevala, Finland’s national epic; on the other, they emerged in the sociopolitical ideologies that developed during the first half of the 20th century, linking beauty to objects that were seen as functional, universal and inclusive. In this manner, the natural world provided the functional, formal and conceptual inspiration for Finnish material culture. This became especially significant after the Second World War, when Finland lost territory to Russia as part of the negotiation to maintain its independence. There was a quest to establish a strong autonomous identity both within the country but also internationally, where it was perceived as being sandwiched between the concepts of East and West.

Within this context, design became an important channel to create a collective identity. Motifs from the Kalevala (which is itself full of sorcery and witchcraft) appear throughout the 20th century within the nation’s architecture, art, and design. To mid-century Finnish designers such as Vuokko EskolinNurmesniemi and Antti Nurmesniemi, design became a “civic duty”, and a way of communicating Finland as an independent Western nation with Finland’s participation in world fairs, triennials and strategic travelling exhibitions. This was also the birth of “Scandinavian Design” as a concept. Although Finland is part of the Nordics, but not Scandinavia, it nevertheless became associated, internationally, with this latter “brand”. Iittala participated in all of these events and many of the iconic products from its current portfolio stem from this era. Design had acquired a heroic role, and this was particularly true of glass. It became an allegorical material through which many of these concepts could be translated.

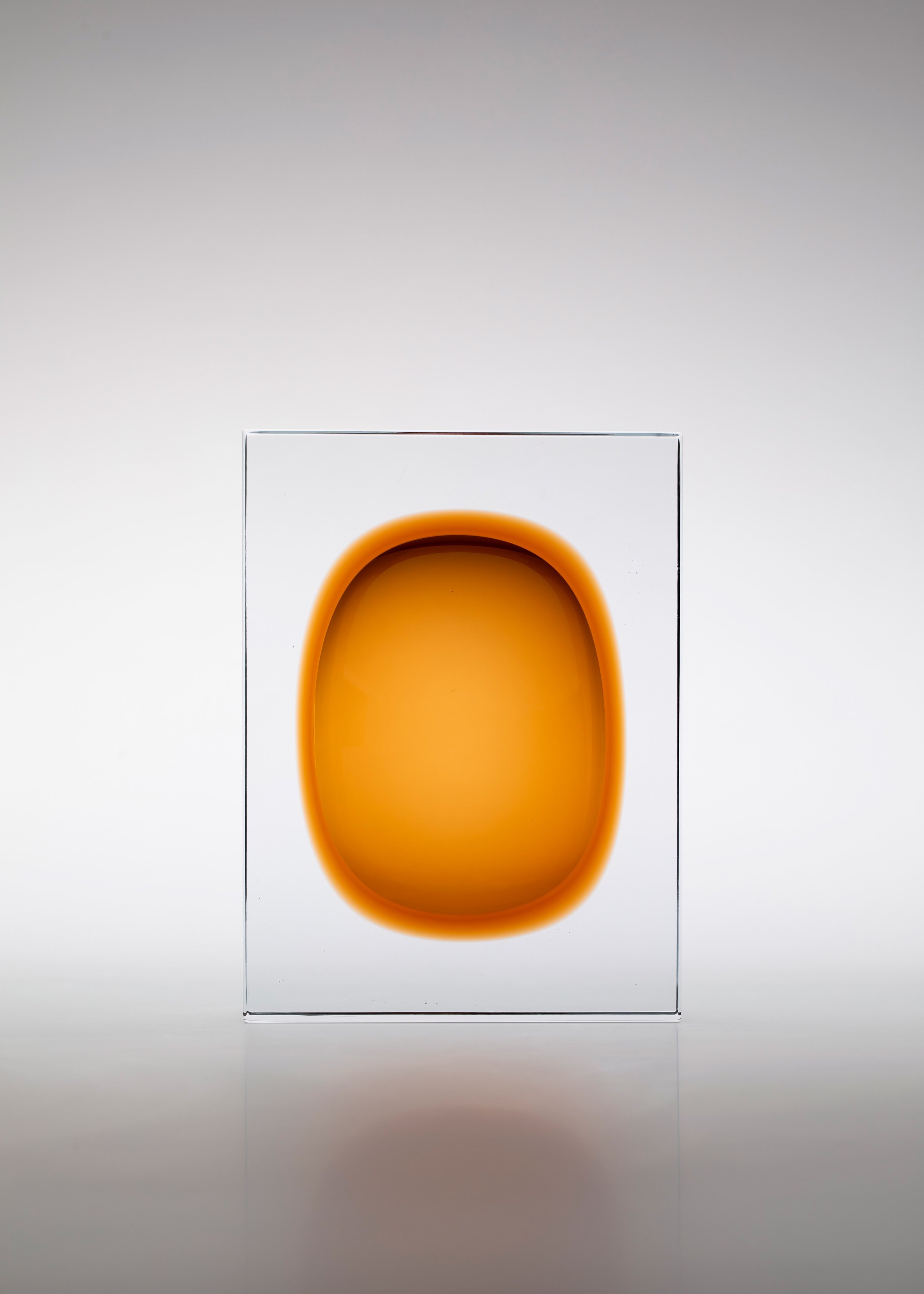

Magic Realism is not just about the past and the Kalevala, however. It’s linked to an element of surprise that is still present today, and which is most obvious if you actually live and work in the factory. In the past, Iittala used to have designers-in-residence, who understood this. Timo Sarpaneva slept on the factory floor during night shifts and Tapio Wirkkala was an in-house designer too. The glassblowers say that these designers truly understood what the possibilities were with glass; what techniques could be used to produce, say, thinner walls and curves; and how to use different colours in different places. We must also consider the new manufacturing technologies that were incorporated to Iittala, such as the centrifugal casting explored by Wirkkala, who actually carved the mould that was then introduced to the factory. Wirkkala often worked from the north of Finland, and many of his works are based on the different states of water. He combined craftsmanship in carving his own moulds, and new experimental technologies such as centrifugal glassblowing, to create everyday wares through serial production. It is a beautiful cycle.

This, of course, feeds into the realism of our Magic Realism. In the 1950s and 60s, Iittala had a strong dedication to creating unique experimental artworks and small editions. However, many of these expressions were then developed to suit designs for daily wares and mass production. Iittala is a brand, as well as a glassworks and a concept, and each of these three aspects have followed different paths. The glassworks have remained relatively unchanged for 140 years, but the brand has merged with different companies, and had many different owners, throughout that same period. For many decades it was actually Karhula-Iittala when Iittala and Karhula (another glassworks) were both purchased by the Ahlström corporation. Many of the works that we know today as part of Iittala, such as Aino Aalto’s Bölgeblick glass, Göran Hongell’s Aarne glass, and, of course, Alvar Aalto’s vases, were actually first produced in the Karhula glassworks. Decades later, Iittala again merged with Nuutajärvi, another icon of Finnish design. So then there was the Iittala-Nuutajärvi brand, through which Kaj Franck and Oiva Toikka were introduced. In 2002, Iittala was reintroduced as a “lifestyle” and finally, in 2007, the Fiskars Corporation took over.

The history of Iittala and KarhulaIittala has a strongly experimental nature, built upon the symbiotic relationship between glassblowers and designers. In our interviews with Iittala’s glassblowers and chemists, there remained a feeling that you can never fully control glass. Even though they’ve been doing this all their lives, and even though the company has been trying to perfect it over the course of 140 years, there’s still an element of surprise and weirdness. Even when a recipe is correct, something unexpected could still happen in the process of blowing the glass – a moment of surprise. The glassblowers, chemists and factory workers all say that they are excited to work with the process of glass manufacture, as it has an element of magic. It is a term that they use as a part of their everyday work, just as Iittala designer Gunnel Nyman did in 1948, when she wrote in an essay that “there is something magical about glass, and no one who comes under its spell can ever leave it”.

When we talk about Magic Realism, it’s not a strict definition. It brings together different elements, some of which belong to Iittala’s history in particular, and others which belong to the history of glassmaking, to Finnish design, as well as to some of the links to nature that have existed from prehistory. This, from our point of view, is something sublime. It is an epic history, and it deserves an epic effort from all to tell it.

Introduction Florencia Colombo and Ville Kokkonen

Images courtesy of the Alvar Aalto Foundation, Eino Nikkilä, Finnish Heritage Agency/Picture Collections and Designmuseo Helsinki.

Based on an original interview with Kristina Rapacki and Oli Stratford.

Iittala – Kaleidoscope: From Nature to Culture was at Designmuseo Finland until 19 September 2021. The exhibition’s book is published by Phaidon, price £59.95.

This article was originally published in Disegno #29. To buy the issue, or subscribe to the journal, please visit the online shop.