Front Did it First

When the Brazilian football legend Pelé (1940-2022) died at the end of 2022, tributes quickly blossomed across YouTube and Twitter. Many of these expressed a similar sentiment. “Everything you see any player doing,” summarised Erling Haaland, one of the sport’s current stars, “Pelé did it first.”

Within design, it is sometimes tempting to wonder if something similar could be said of Front, the Stockholm-based studio of Anna Lindgren and Sofia Lagerkvist. The studio is this year’s Guest of Honour at the Stockholm Furniture Fair, the first time in the fair’s history that the honour has been bestowed upon a Swedish practice, and the event provides a good excuse to look back through the projects that the practice has developed since its foundation in 2004. The results are eerily prescient.

Take Representation of things (2005), a video game that Front developed to explore what it might mean to design for digital space, and the manner in which objects are mediated through imagery – a project that preempted mainstream design’s current debates around the metaverse by close to 15 years. Or Sketch (2005), a collection of 3D-printed furniture pieces that were created by using motion capture technology to record the movements of a pen sketching in 3D space – an investigation of technologies that are now familiar within the field, but which went largely unheralded within design production in the early 2000s. Or how about more-than-human design, an emerging area of practice that acknowledges the potential hubris of a human-centric approach? As early as 2004, Front was playing around with similar ideas in Design by Animals, a homeware collection that delegated creative agency to dogs, rats, beetles and snakes as a means of highlighting the absurdity of designers professing to be in full control of their craft. Whichever area of contemporary design falls within the current zeitgeist, there’s a good chance that Front did it first.

“We’ve always been curious about the different stories around objects, and focused on things that perhaps weren’t common at the time, but which now feel very relevant to design.”

“The most interesting thing for us has been to see the change in the value attributed to these projects,” says Lagerkvist, who together with Lindgren is exhibiting a selection of Front’s past and current projects in an installation that will greet visitors in the entrance hall to the Stockholm Furniture Fair, hosted in the city’s Stockholmsmässan in February 2023. “We’ve always been curious about the different stories around objects, and focused on things that perhaps weren’t common at the time,” Lagerkvist continues, “but which now feel very relevant to design.”

It is an important point, particularly given that many of Front’s works proved divisive upon release. The studio’s Horse Lamp (2006) for Moooi – a life-size plastic horse with a lamp sprouting from its head – is perhaps Front’s most recognisable work, debuting at the 2006 Salone del Mobile. Today, it features in the permanent collection of the Vitra Design Museum, celebrated as a design that challenged the field’s hostility towards figurative forms, and which probed at static notions of tastefulness within design. But the lamp was heavily criticised upon launch, with Sweden’s Dagens Nyheter newspaper displaying a photograph of the design under the headline “Death in Milan”. “We realised this was an object to either love or hate,” Lagerkvist recalls. The fact that the piece has subsequently been embraced by the canon, Lagerkvist suggests, is demonstrative of a positive growth in the discipline’s acceptance of different approaches, styles and values. “The design scene now looks completely different to how it did back then,” she says. “If you were to release that piece today, it would be totally different because there is so much more variety as to what design can be.”

“The design scene now looks completely different to how it did back then. If you were to release that piece today, it would be totally different because there is so much more variety as to what design can be.”

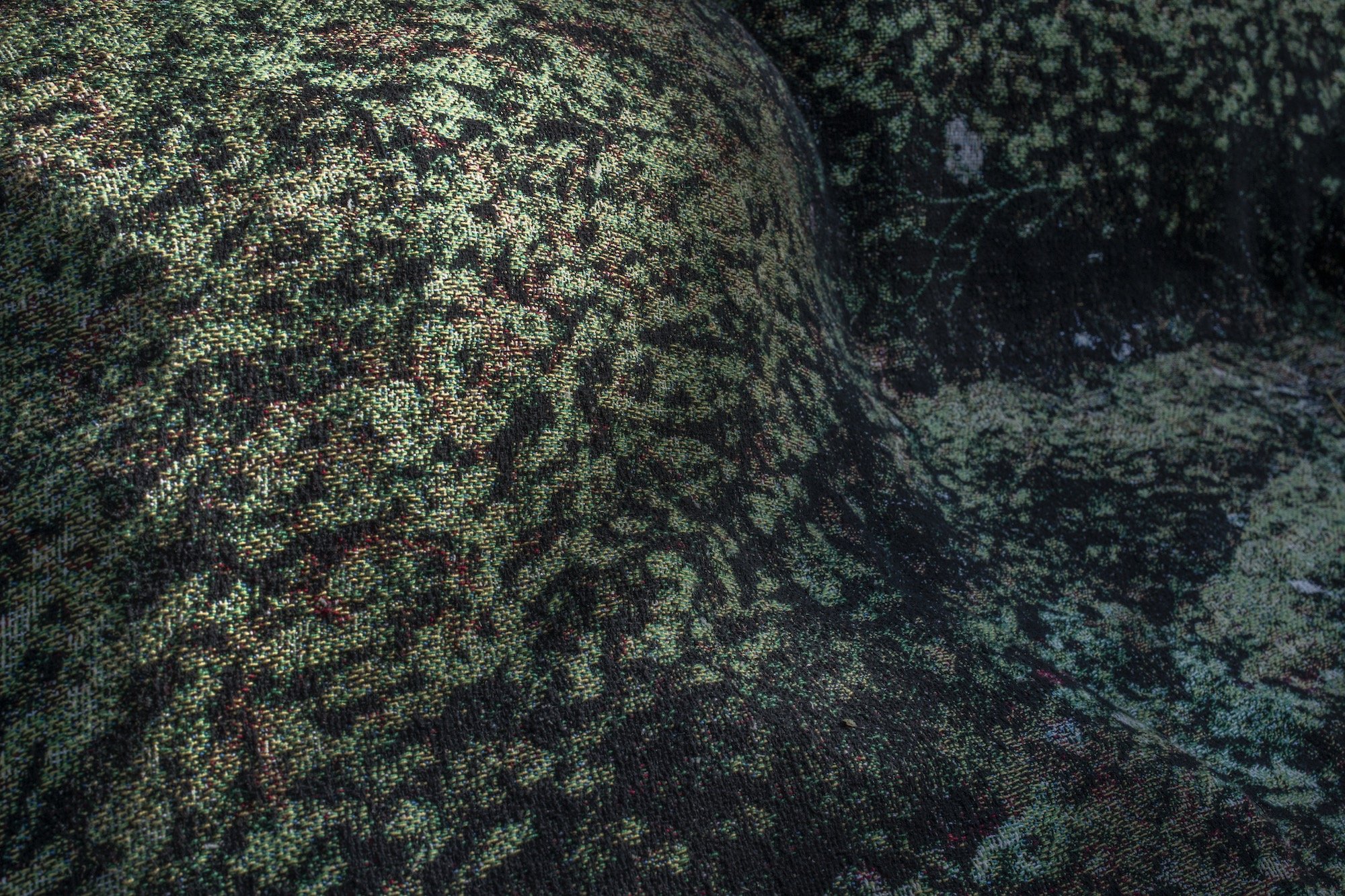

This, of course, is what makes Front a compelling choice for the Stockholm Furniture Fair. Throughout its existence, the studio has moved freely between the design of commercial furniture, lighting and objects, and the development of self-initiated research projects. While the outcomes reached by these strands of Front’s work may be different, the processes that generate them blur together. The studio’s Pebble Rubble (2022) furniture for Moroso, which recasts the forms of 3D-scanned boulders as indoor seating, was not planned from the outset as a work of industrial design, but rather emerged through the studio’s wider Design by Nature (2020) project – an open-ended investigation into natural landscapes and the ways in which they might be reinterpreted within design work. Conversely, Front’s Story Vases (2011) were developed as an investigation of craft traditions within KwaZulu-Natal in South Africa, but found fulfilment as a project when they resulted in saleable objects that could provide a stable income for the Zulu women who produce them. “You start down a path and you never know where it’s going to take you,” Lagerkvist summarises. Within the context of a design fair, Front’s career proves a fascinating study of the manner in which commercial design and research-based practice can prove mutually beneficial. In Front’s work, the two fields are not sharply divided, but rather flow into one another, frequently shaping the direction of projects as they shift between contexts. The studio’s Melt lamp (2015) for Tom Dixon and Resting Animals (2018) collection for Vitra have both proven commercially successful, for example, but each grew out of research concerns that appear throughout Front’s wider practice: the potential for nature to inform industrial design, and the potential for figurative objects to provide companionship and solace. “We’re interested in the transformation of an object in a project,” Lagerkvist states. “It starts as something very specific and then shifts as you carry out research and development.”

These ideas are worthy of consideration during Stockholm Furniture Fair, an essential element of the annual design calendar that is now returning following a two-year absence as a result of Covid-19. While societies around the world have been forced to function under lockdowns and travel restrictions, and amidst concerns about the feasibility of large-scale events hosted the pandemic, the design industry has adapted accordingly, with the resultant emergence of digital platforms prompting reflection around the role of in-person fairs moving forward. Stockholm’s return, however, is not only an indication of the enduring importance of the trade fair format to business, but also an exploration of the way in which such events can help to promote critical and curatorial engagement with the field.

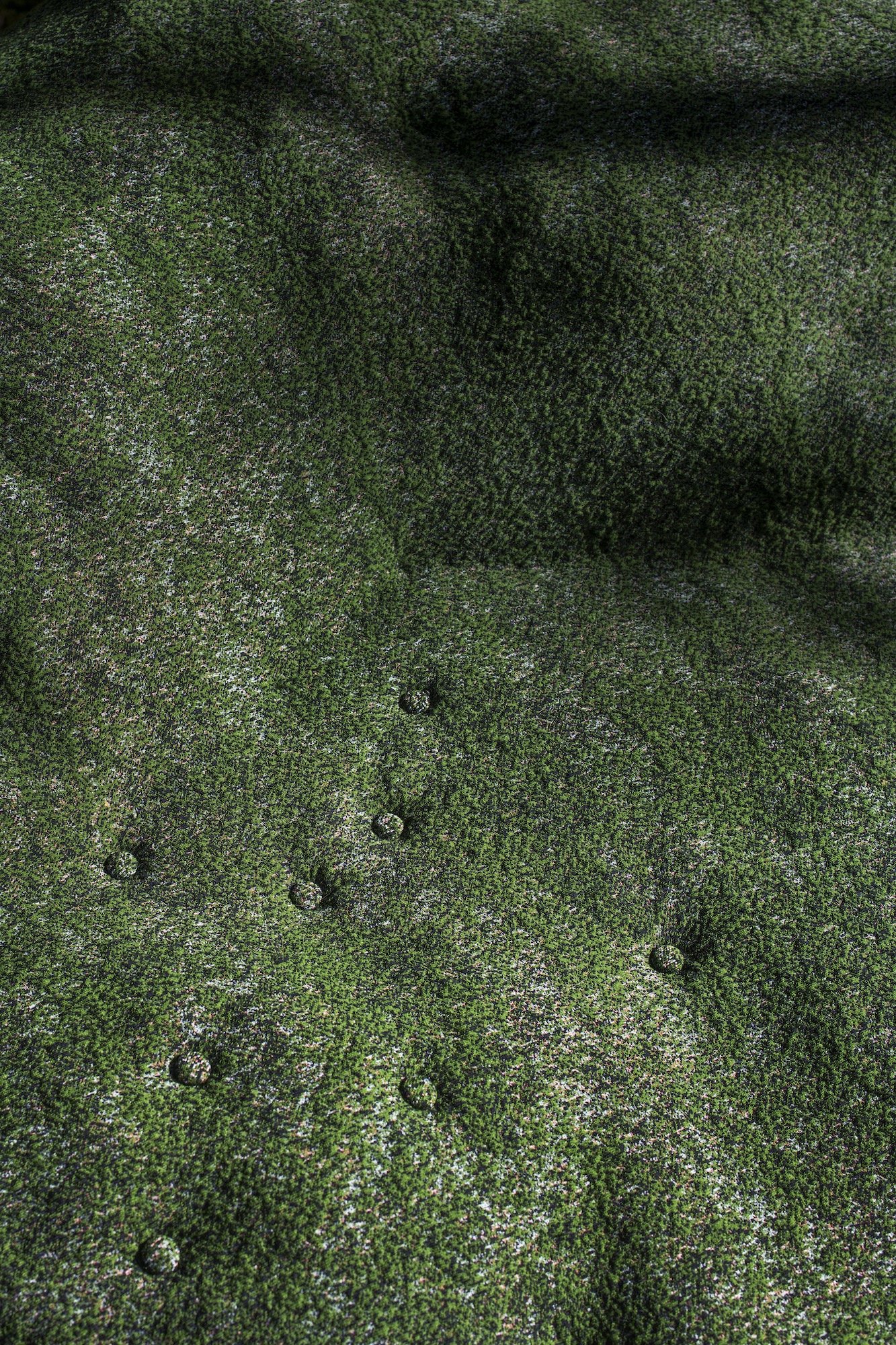

Front are fine ambassadors for this two-pronged approach, their work straddling both sides of the discipline, but so too is the fair's wider programming. This year’s edition includes talks such as Stephen Burks on race, domesticity and design, Sabine Marcelis on material cultures, and Borys Dorogov on architecture’s potential response to the war in Ukraine; and a new element to the event, Älvsjö Gård, which is devoted to the display forms of design practice which shift the discipline outside of industrial production. There is also the Nude Edition, an experimental display format in which a section of the fair will feature stands that share a uniform design produced using a recycled and recyclable material. It represents a practical solution to improving the sustainability of the event, whose debut in 2023 may serve as a pilot for future editions of the fair. Crucially, the fair has also launched a new app (available through Google Play and the Apple App Store), which will help to guide visitors to the fair between the wider series of events, exhibitions and activities hosted around the city as part of the concurrent Stockholm Design Week – a means of connecting up different approaches and manifestations of design as part of one overarching festival.

It is an inquisitive, open-minded approach towards design, and one for which Front are standard bearers: as Lagerkvist notes, the studio’s overarching interest within its work has been to “dissect the idea of being a designer”. As the Stockholm Furniture Fair prepares to relaunch and provide a new forum for reflection on what it means to work as a designer today, it is worth remembering one thing – Front probably did it first.

Words Oli Stratford

This article was made for the Stockholm Furniture Fair